We will turn common intuitions about happiness into a formula in this post. What we aim to calculate is, strictly speaking, an objective measure of wellbeing. But “happiness calculator” just sounds better; “wellbeing calculator” is a mouthful.

Let’s start with some intuitions. As I wrote in an older post, ‘health’, ‘love’, ‘respect’, and ‘wealth’ are examples of basic human needs. These are not the only human needs, but a set of sample “inputs” to show how the happiness calculation works.

Since a calculation requires numbers, we need a way to convert ‘health’, ‘wealth’ etc. into numbers. To keep things objective, we will use percentiles as inputs. For example, if I am wealthier than 70% of people (such data is often found in census reports), then I would enter 7/10 or 0.7 as my wealth score. For ‘health’, ‘love’ and ‘respect’, the scores are answers to the questions: I am healthier/more loved/more respected than what fraction of people? There can be no universal agreement on measuring love, respect, or even health. So, guess your answer. Give yourself a score.

Our wellbeing depends on all of these scores, which naturally points to some kind of an average. But a simple average (arithmetic mean) won’t do. Let’s examine why.

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Anna Karenina

The above quote is from Leo Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina. Why are happy families alike, yet unhappy families dissimilar? The answer lies in the diversity of human needs. Happy families have all basic human needs met, which makes them similar. On the other hand, unhappiness can result from the absence of any single basic necessity. A family can be intensely unhappy because someone is dying of disease. Another family can be very unhappy because of marital discord. A third family may be in extreme poverty.

The problem with an arithmetic average is that it does not allow any single need to dominate overall wellbeing, which it should in this case. Using a geometric average instead of an arithmetic average solves this problem. If any single input to a geometric average is zero, the average itself becomes zero. This resembles human wellbeing: if a single fundamental need is not met, a person can become miserable.

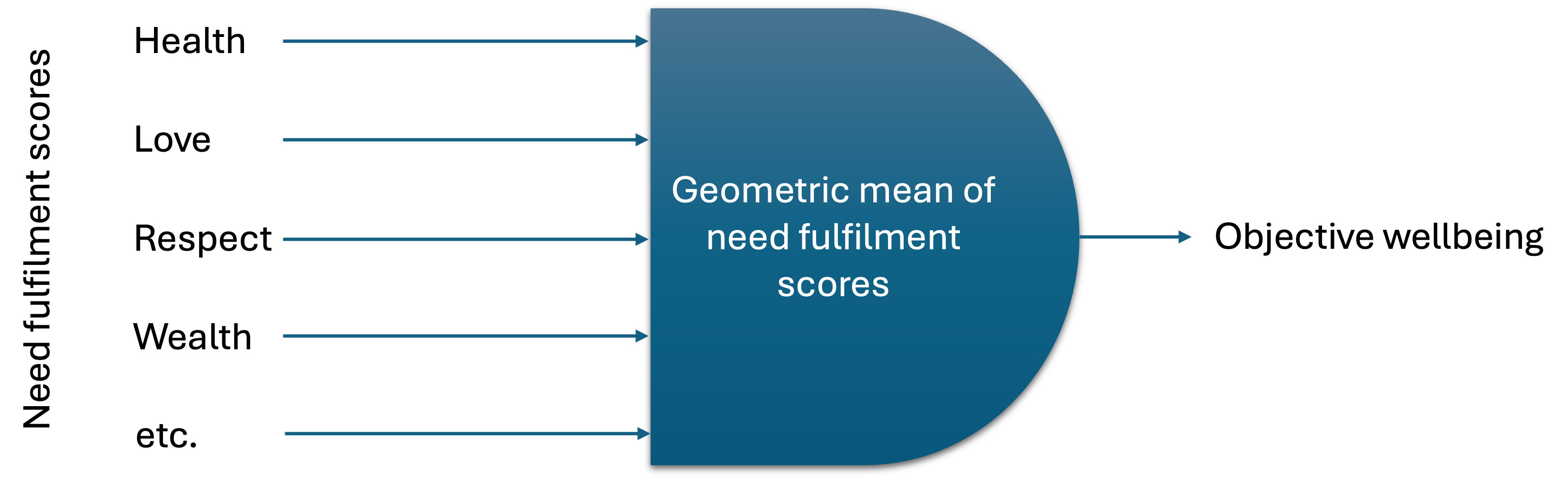

Putting all this together, our simple happiness calculator looks like this:

This calculation model says that wellbeing is the geometric average of the degree to which basic needs are met. For the mathematically inclined, log( wellbeing ) = average( logs of basic need scores ) ).

Let’s look at an example. If you are healthier than 30% of people, more loved than 60%, more respected than 80%, and wealthier than 70%, then your wellbeing is (30/100 * 60/100 * 80/100 * 70/100)1/4 = 56%. This isn’t a bad score. Anything above 50% means that you are happier than the median human being. Although.. that may not be how you “feel” – that is where subjectivity comes into the picture.

On another note, can you score someone else’s happiness using this method, someone you know well, or a well-known celebrity perhaps?

In the interest of avoiding a very long post, I’ll stop here. There’s more to come: the role of our attitude, lessons from the lives of others, and what steps we can take to make our lives better.