“The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven..”

John Milton

In earlier posts, I have talked about “objective” wellbeing; how to calculate it, and how to improve it. But how happy we feel can be quite different from our objective reality. A person can become depressed for something seemingly trivial to others but overwhelmingly important within the confines of their own mind.

As a species, we have evolved to gradually dominate our surroundings. An animal in the wild spends most of its energy on food and survival. This was also true of primitive humans who were hunter-gatherers for several hundred thousand years. Agriculture, which was invented around ten thousand years ago, increased our food supply, which must have also freed us up to pursue non-essential activities.

The idea that our wellbeing is something we can control with our mind is grounded in a reality where our primal feelings are no longer essential for survival. This idea is central to Buddha’s teachings from over 2500 years ago. Buddha taught that suffering is caused by craving and can be ended by getting rid of behaviors such as greed, hatred and ignorance. What other religions say is similar in essence: avoid behavior that may have aided survival in the jungle but that will get you into trouble in civilized human society. In short, train your mind.

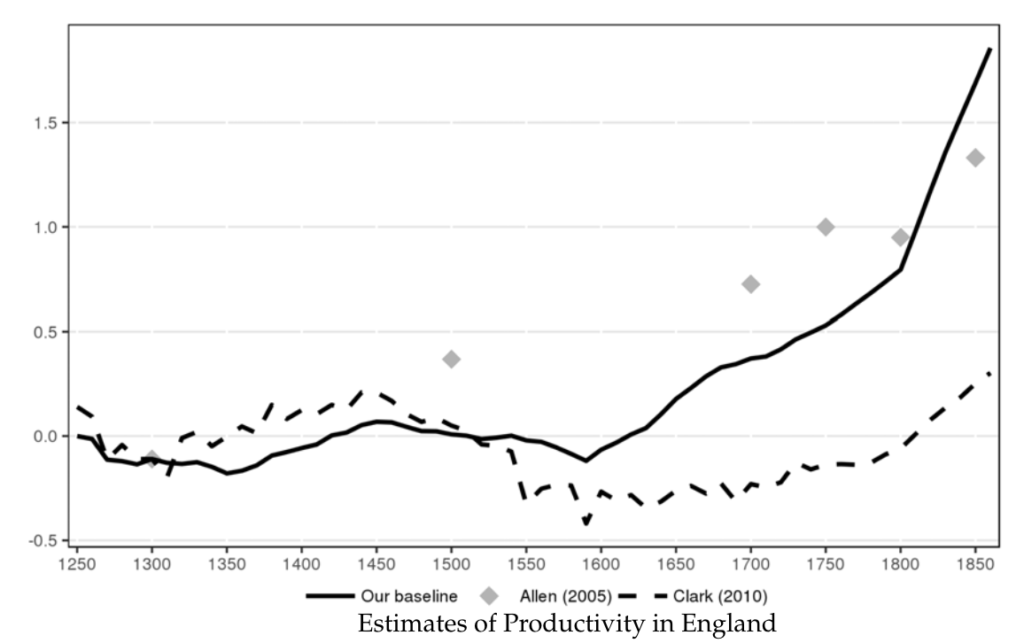

The industrial revolution, which is just a few hundred years old, improved human productivity dramatically. We can see this in data from England:

Interestingly, this increase in productivity went hand-in-hand with humans spending more time working:

Advances in technology have made us more efficient, but we still work more hours than we did as hunter gatherers. We don’t have to, but we do. As our lives improve, we become accustomed to a better life, something called hedonic adaptation. And then we want an even better life. This is great for progress, but can lead to dissatisfaction when higher expectations are not met.

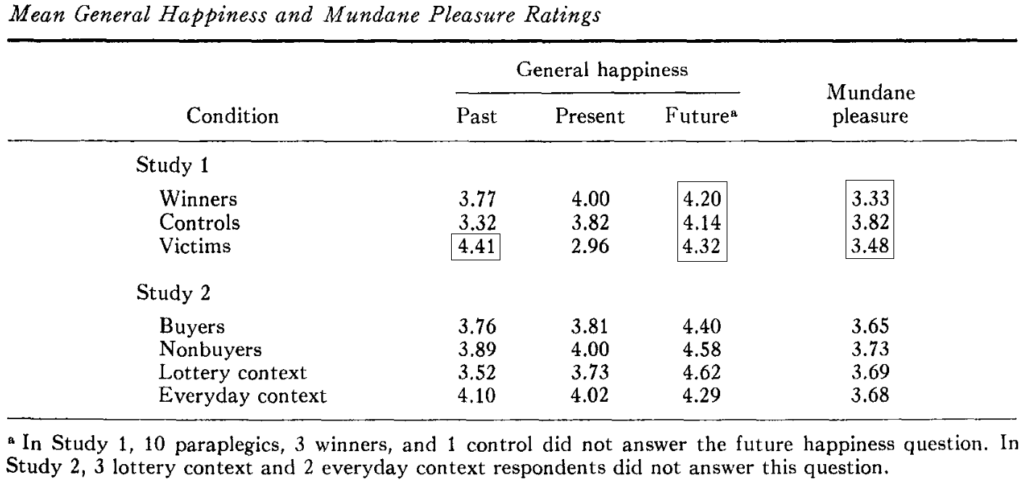

Thankfully, hedonic adaptation works both ways: we adjust to negative experiences as well as positive. Just how powerful our mind is in shaping our subjective happiness can be appreciated through a well-known, and quite old, study of lottery winners and paralyzed accident victims. In this study, researchers found that paralyzed accident victims estimated their “future general happiness” and “pleasure found in mundane events” to be slightly higher than the lottery winners! The table below shows the results, where I have boxed the relevant numbers.

Relative?

The happiness estimates of accident victims were not a lot higher, but even if comparable, it is stunning to think that a person imagines themself as happy in the future when they experience a paralysis-causing accident as compared to when they win a major lottery.

Another observation from the same study was that “accident victims recalled their past as having been happier than did controls (which we may call a nostalgia effect)”. Does a crippling accident make us more grateful for the life we had? It probably does.

It would be fair to conclude that we can be happy with a lot less in life. Having a lot less does not meaningfully lower our chance of survival in the modern world. However, the right way of thinking can make us feel a lot happier.